![]()

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY 17 SEPT 12:00

(LONDON TIME)2013年9月17日倫敦時間1200全球同步發布 ![]()

全球三分之二的國會未能成為國防貪腐的監督者

國際透明組織最新研究發現85%的國會缺乏對國防政策有效的監督

國際透明組織最新評比全球82國出爐,台灣在全球國防貪腐的國會監督評比之中被列為第二等之低貪腐風險(Low)。台灣立法院對於國防預算之控制與影響力受到本研究報告之肯定,該報告第30頁引台灣為範例認為立法院國防委員會以要求政府提出報告與備詢善盡監督政府之責。此外,國防委員會以網路實況轉播議程促進國防預算之透明度。不過台灣國防機密預算(45頁)與情治單位之監督(49頁)尚待加強。本研究之評比作業係於2012年春天完成,國際透明組織對於本(2013)年洪仲丘案引發之國軍制度變革成效表達關切,正偕同台灣透明組織共同努力,持續觀察台灣國防部之改革成效。

比利時, 2013年9月17日—國際透明組織英國分會國防安全計劃小組(Transparency International UK’s Defence and Security Programme , TI-DSP)最新報告主題為「監督者」(英文全文請參見附件)指出,三分之二的國會和立法機構未能對其國防部及武裝部隊發揮足夠的控制力。此外,2012年最主要武器進口國之中70%對於貪腐門戶洞開未設防。

本研究,係2013年「政府國防廉潔指數」(Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index, GI)中所得出來的延伸成果,該指數針對82個國家如何在國防部門降低貪汙風險之作為進行了分析,包括根據國會在七大領域所扮演的重要反貪污角色進行詳細評估,並且將這些受評國家分別列於不同的貪汙風險級別。

14個國家之國會監督表現居末段,包括阿爾及利亞、安哥拉、喀麥隆、象牙海岸、剛果民主共和國、埃及、厄立特里亞、伊朗、利比亞、卡達、斯里蘭卡、沙烏地阿拉伯、敘利亞和葉門等國,因缺乏立法部門對國防的監督而有極高的貪污風險。僅有澳大利亞、德國、挪威和英國等四國,因極低(Very Low)的貪腐風險而使表現優於其他國家居於首位,次優的台灣等12個國家則因相對比其他受評國國會有較好的表現而被置於低風險等級(Low)。

國際透明組織英國分會國防安全計劃小組主任馬克•白曼(Mark Pyman)說明:「國防貪腐具有危險性、分裂性與浪費性,其貪腐成本卻由士兵、企業、政府和公民買單。大部分的立法機構都是失敗的投票部隊,因無法扮演對於此重大部門的適宜監督。不論其中的問題出在政治環境、劣質的立法或國會議員未能實踐承諾,本研究中之各國實踐範例皆可幫助其他國家借鏡改善之。」

根據世界銀行(the World Bank)和斯德哥爾摩國際和平研究所(Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI)的資料,國際透明組織英國分會國防安全計劃小組估計全球每年在國防部門之貪腐至少損失掉二百億美元,這個金額遠超過加拿大及英國在2012年所提供的國際發展援助總和。

1

![]()

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY 17 SEPT 12:00

(LONDON TIME)2013年9月17日倫敦時間1200全球同步發布 ![]()

強大的軍方,缺乏監督導致浪費與卸責

在以高價合約及高度秘密為特徵的國防部門下,國會及立法機關可以藉由通過預防法令、將國防貪腐議題放置到國家討論層次,以及執行監督權的方式來防止貪污風險。全球受評過之中85%的國會缺乏對國防政策有效性的、問責性的、及全面性的監督。本研究報告全文於今日全球同步公布之外,稍晚在比利時布魯塞爾的安全與國防議程論壇上(Security & Defence Agenda)進行討論。白曼主任表示:「這使得貪腐有機可乘,脫離大眾監督機制視線之外,而浪費了本應可較好使用到別處去的資金。」

本研究認為總統制國家比起非總統制者具較高的貪腐風險。軍隊人數佔較高的人口比例時似乎亦容易增加貪腐,因為較大的武裝力量可能具有更強的影響力和對決策者的遊說能力,進而阻礙國會對國防部門的監督。

國際透明組織呼籲國會議員建立組織跨黨委員會及外部專家團體,以增強國會監督權能並且隨時告知在國防事務上的相關辯論內容。

前南非國會議員安德魯·范斯坦(Andrew Feinstein)對本「監督者」報告有如下評論:「立法機關以犧牲公民的福祉為代價,對國防監督已忽略太久。藉由向各國國會議員展示改進之道,這份報告是克服國會長久以來疏於監督國防的重要一步。”

編者按:

1.在本「監督者」報告中,國際透明組織的國防團隊指出國會可在七個面向降低國防貪腐:

a預算監督與討論

b預算透明度

c外部審計

d政策監督與討論

e秘密預算監督

f情報機構監督

g採購監督

2.團隊所確認的此七個面向,是經由節選2013年「政府國防廉潔指數」中所使用的19個指標資料,以及適度補充更新此指數中的質性分析分數所解析出來的,此報告包涵台灣等19個國家案例研究以強調特定的優良實踐,亦做出明確的建議及提出實際的工具,以使此範例可在其他國家被複製。

3.國際透明組織英國分會國防和安全計劃小組(TI-DSP)透過支持各個國家的反貪污改革,提高軍火轉移中的自律和在國防和安全上影響政策的制定來幫助您建立廉政體系,減少全球國防和安全機構中的貪污。TI-DSP聯合各國政府,國防企業,跨國組織和公民社會組織共同合作來達到這個目的。TI-DSP的詳細情況,請點閱www.ti-defence.org網站。

附件1:結果

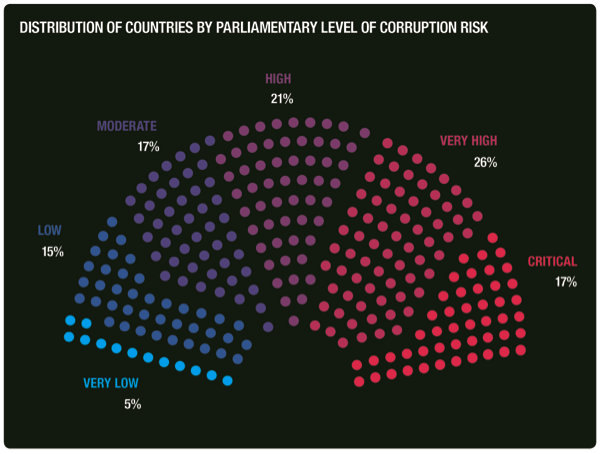

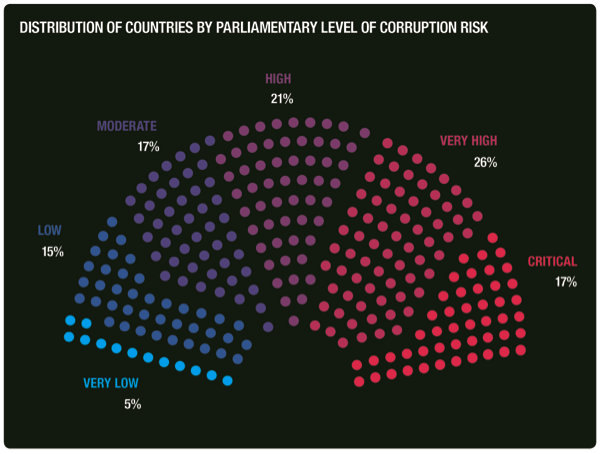

以下是把82國依據國會議場座位表進行排序【國家在貪腐風險國會等級上的分布狀況】

2

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY 17 SEPT 12:00

(LONDON TIME)2013年9月17日倫敦時間1200全球同步發布 ![]()

風險極低(VERY LOW, 4國): 澳大利亞,德國,挪威,英國

風險低 (LOW, 12 國): 奧地利, 巴西,保加利亞,哥倫比亞, 法國,日本,波蘭,斯洛伐克,南韓,瑞典,臺灣,美國

中度風險 (MODERATE ,14 國): 阿根廷,波士尼亞與赫塞哥維納,智利,克羅埃西亞共和國,塞普勒斯,捷克,匈牙利,義大利,拉脫維亞,墨西哥,南非,西班牙,泰國,烏克蘭

風險高 (HIGH , 17 國): 喬治亞,迦納,希臘, 印度,印尼,以色列,哈薩克,肯亞,科威特,黎巴嫩,尼泊爾,菲律賓,俄國,塞爾維亞,坦尚尼亞,土耳其,烏干達

風險很高(VERY HIGH , 21 國): 阿富汗, 巴林,孟加拉共和國,白俄羅斯,中國,衣索比亞,伊拉克,約旦,馬來西亞,摩洛哥,奈及利亞,阿曼,巴勒斯坦,巴基斯坦, 盧安達,新加坡, 突尼西亞,阿拉伯聯合大公國,烏茲別克斯坦,委內瑞拉,辛巴威

風險極高 (CRITICAL ,14 國): 阿爾及利亞,安哥拉,喀麥隆,象牙海岸,剛果民主共和國, 埃及, 厄立特里亞,伊朗,利比亞,卡達,斯里蘭卡,沙烏地阿拉伯,敘利亞, 葉門

3

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY 17 SEPT 12:00

(LONDON TIME) ![]()

Two-thirds of parliaments fail to be watchdogs of defence corruption

New study by Transparency International also finds 85% of them lack effective scrutiny of defence policy

Brussels, 17 Sept 2013—Two-thirds of parliament and legislatures fail to exercise sufficient control over their Ministry of Defence and the armed forces, according to a new report by Transparency International UK’s Defence and Security Programme (TI-DSP). Amongst those, 70 per cent of the largest arms importers in 2012 leave the door open to corruption.

The study—a spin-off from the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index 2013 (GI) which analysed what 82 countries do to reduce corruption risks in the sector— places countries in corruption risk bands according to detailed assessments across seven areas in which parliaments play a vital anti-corruption role. It also shows, through detailed case studies, how parliaments and legislatures can improve oversight of defence.

Fourteen countries were placed at the bottom of the banding, exhibiting critical risk of corruption due to lack of legislative defence oversight: Algeria, Angola, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Libya, Qatar, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen. Only four nations—Australia, Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom—were amongst the top performers, with very low levels of corruption risk, followed by twelve countries which are at low risk due to better performance by their parliaments.

“Corruption in defence is dangerous, divisive and wasteful, and the cost is paid by soldiers, companies, governments, and citizens. Most legislatures are failing voters by not acting as proper watchdogs of this huge sector. Whether the problems are due to the political environment, poor legislation, or poor commitment by parliamentarians, the good practice examples in this study can help them improve,” said Mark Pyman, Director of TI-DSP.

TI-DSP estimates the global cost of corruption in the defence sector to be a minimum of USD 20 billion per year, based on data from the World Bank and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). This is more than the combined international development aid provided by Canada and the UK in 2012.

Powerful militaries, lack of oversight linked to waste and impunity

In a sector characterised by high-value contracts and secrecy, parliaments and legislatures can prevent the risk of corruption by passing laws to prevent it, putting issues of corruption in defence at the level of national debate, and exercising powers of oversight. Yet 85 per cent of them lack effective, accountable and comprehensive scrutiny of defence policy according to the report, ‘Watchdogs?’, which is being launched today with an evening debate in Brussels hosted by Security & Defence Agenda. “This provides opportunities for corruption to be hidden away from mechanisms of public scrutiny, and wastes money that could be better spent elsewhere,” said Pyman.

The study suggests that presidential systems are at higher risk of corruption than non-presidential systems. Corruption also seems to increase when members of the military make up a greater portion of the population, as larger armed forces may have stronger influence and lobbying power with decision-makers, undermining parliamentary oversight of the sector.

Transparency International calls on parliamentarians to establish cross-party committees and groups of external experts to empower their scrutiny and inform their debate of defence matters.

Commenting on ‘Watchdogs?’, former South African MP Andrew Feinstein said: “Legislative oversight of defence has been neglected for too long at the expense of the well-being of citizens. By showing parliamentarians how they can improve, this report is an important step in overcoming this historical neglect of defence oversight”.

-ends-

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY 17 SEPT 12:00

(LONDON TIME) ![]()

Note to editors:

1.In “Watchdogs?” Transparency International’s defence team identified seven areas in which parliaments may reduce corruption in defence:

a. Budget oversight & debate

b. Budget transparency

c. External audit

d. Policy oversight & debate

e. Secret budgets oversight

f. Intelligence services oversight

g. Procurement oversight

2.The seven areas identified by the team were analysed by cutting the data from 19 of the indicators used in the GI 2013, and by supplementing the scores with qualitative analysis from the GI assessments, updated appropriately. The report contains 19 country case studies to highlight specific good practice. It also makes clear recommendations, and proposes practical tools, by which this good practice can be replicated in other countries.

3.Transparency International UK’s Defence and Security Programme helps to build integrity and reduce corruption in defence and security establishments worldwide through supporting counter corruption reform in nations, raising integrity in arms transfers, and influencing policy in defence and security. To achieve this, the programme works with governments, defence companies, multilateral organisations and civil society. The programme is led by Transparency International UK (TI-UK) on behalf of the TI movement. For more information about the programme please visit www.ti-defence.org.

–

–

ANNEX 1: OVERALL RESULTS

If the countries analysed were parliamentarians, and the levels of corruption risk they displayed were political parties, the distribution of seats in the global parliament would look like the image below.

VERY LOW (4 countries): AUSTRALIA, GERMANY, NORWAY, UNITED KINGDOM

LOW (12 countries): AUSTRIA, BRAZIL, BULGARIA, COLOMBIA, FRANCE, JAPAN, POLAND, SLOVAKIA, SOUTH KOREA, SWEDEN, TAIWAN, UNITED STATES

MODERATE (14 countries): ARGENTINA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, CHILE, CROATIA, CYPRUS, CZECH REPUBLIC, HUNGARY, ITALY, LATVIA, MEXICO, SOUTH AFRICA, SPAIN, THAILAND, UKRAINE

HIGH (17 countries): GEORGIA, GHANA, GREECE, INDIA, INDONESIA, ISRAEL, KAZAKHSTAN, KENYA, KUWAIT, LEBANON, NEPAL, PHILIPPINES, RUSSIA, SERBIA, TANZANIA, TURKEY, UGANDA

VERY HIGH (21 countries): AFGHANISTAN, BAHRAIN, BANGLADESH, BELARUS, CHINA, ETHIOPIA, IRAQ, JORDAN, MALAYSIA, MOROCCO, NIGERIA, OMAN, PALESTINE, PAKISTAN, RWANDA, SINGAPORE, TUNISIA, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, UZBEKISTAN, VENEZUELA, ZIMBABWE

CRITICAL (14 countries): ALGERIA, ANGOLA, CAMEROON, COTE D’IVOIRE, DRC, EGYPT, ERITREA, IRAN, LIBYA, QATAR, SRI LANKA, SAUDI ARABIA, SYRIA, YEMEN

Watchdogs?The quality of legislative oversight of defence in 82 countries Executive summary

Watchdogs?The quality of legislative oversight of defence in 82 countries